LOW SHELVES AND HIGH SHELVES

When this lonely writing life sucks me down, I look to my books for solace. I kneel first by the lower shelves, home to racier friends, legendary abusers of the literary life, and quietly binge.

I binge on London and Bishop, Faulkner and Sexton, Fitzgerald and Fallada, Dazai and O’Neill, who tragically said, ‘I only feel alive when I am drinking.’ I take Moscow to the End of the Line from the shelf. Written by the Russian, Venedikt Erofeev, it charts the drunken demise of his chain-smoking persona, Venichka, riding a train to visit his lover in Petushki, the last stop village. Venichka drinks and carouses with his friends in the carriages. He delivers soaring sermons on politics and society, on the powers of drink, on the agonies of love. When the vodka runs out, Venichka and comrades turn to potentially lethal cocktails involving boot polish and weed killer.

Erofeev had many jobs, one of which was cable laying for a phone company. (Imagine the misery of the job during the icy winters. Probably sufficient to turn any man to drink, let alone a writer.) Erofeev chronicled his poetic self-destructiveness so famously that the motherland immortalised him with a statue in Moscow’s Struggle Square. How cockeyed and ribald – a nation state honouring its drunkards. But this drunkard wrote a beautiful book, and we are talking Russia here, with its brutal history and weather and its weakness for vodka. The millions of soldiers who turned back the Nazis received a daily vodka ration. Perhaps the French would have fared better in WW2 if their Maginot soldiers had been fortified.

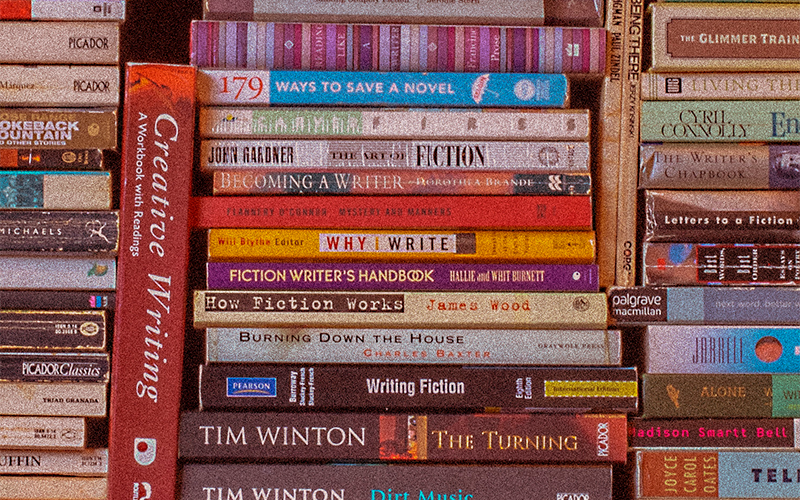

I get off my knees and consider higher shelves. I reach for Jerome Sterne, Janet Burroway, Peter Selgin and Rainier Maria Rilke, who offer me supreme writerly guidance.

In Letters to a Young Poet, Rilke outlines some tenets for rendering the writer’s life manageable and productive. Franz Xaver Kappus, a lost poet, sought help from Rilke in 1903. Rilke responded. The book, arranged in ten letters, captures truths a master shared with his apprentice. He speaks of the need for distance from public opinion, for the wisdom of nature, for visiting interior places to consider what requires written expression, uber alles. He writes of his artistic heroes – the Danish writer, Jens Peter Jacobsen, and the sculptor, Augustin Rodin. He writes of the merits of solitude and nature, the innocence of childhood, and the difficult process of learning to love another. And he says writers must pursue their craft with a sense of boundless freedom, as if they had already died, or as if nobody else existed.

For me the above-mentioned nobodies are primarily the chattering voices of mainstream society – drive-time radio hosts, much of what passes for news and television programs, and their yoking to mind-numbing adverts. It’s hard for us to ward off gung-ho opinion makers, agenda shapers, even if we see a need to. Nobody likes relegation to the margins. We want to chip in at the dinner party, at the water cooler, to share out take on x or y, to be zeitgeisty!

But: Not so for the artist trying to till new ground. To defend his soul in the age of cable television, the internet and social media. To avoid the zeitgeisty!

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.