15 Essential Books

FIFTEEN ESSENTIAL BOOKS ON CREATIVE WRITING

- Introduction

The danger lurks: having studied books on writing, having carted off barrows of advice, trouble confronts you on the page. Here’s the scenario: You lay down a nine-word sentence and then subject it to a checklist of do’s and don’ts assembled from your reading. The sentence falls shy of checkpoints 16 and 43. You discard it and write another, which falls shy of 5 points. After too much of this, you yell and curse and prepare to throw out the writing books that were meant to inspire you.

Here’s an idea: how about throwing out the list of checkpoints?

Okay. Let’s turn to your instincts – those honed from years of reading and writing. Let’s consider in a measured, cherry-picking kind of way – given space constraints – some steps required for the writing of poems, stories and novels that please you and others.

Up front is the need to give ourselves permission to write badly – so says Stephen Dobyns, highly regarded writer of novels, story and poetry collections and more. We don’t have to like the sentences we first lay down, he says, what counts is having something on the page to work with.

Appreciating now that a large part of writing is rewriting, we realise our work will only achieve clarity, concision and heft on the page after many drafts. The knowledge it’s only a draft is invaluable, for it allows us to write free of inhibitions. We have licence to experiment on the page, to have characters fly if we wish and to write the story we once thought too delicate to ruin by actually writing. One caveat here – we must be wary of the managerial left side of the brain bullying the creative right side. Let’s lock out the left side for now – he has no role to play in our early drafting. Later he can come out and respectably vet our narrative choices – why really did the right brain choose a tow truck driver for that scene and should she and her high-powered truck remain in that strand of the narrative?

The writing continues. We establish a comfortable routine and over time a revelation comes: we are subliminally honouring those checkpoint items of old, those pseudo-rules that once undermined our creativity and pleasure in shaping sentences and building narratives.

Now it’s different. We once read that dialogue must perform a number of functions in a story or it will seem threadbare. We have come to know this instinctively and the fruits of our knowledge are even beginning to show in our first drafts. Our dialogue is multi-tasking. It’s earning its keep. One exchange charges the narrative, characterises and propels the story, another shows motivation, delivers humour and triggers change.

As we draft, we try to maintain a thrust and energy, the same energy that fuels ‘My Struggle’, the wildly successful autobiographical novel in six volumes by Norwegian writer, Karl Ove Knausgaard. He writes about the struggle of daily family life, the minutiae, such as negotiating with a spouse, taking the children to play dates and finding time to write. This prosaic subject matter, autobiographical to boot, is not normally associated with high-octane storytelling, but Karl Ove succeeds and does so over six volumes! How is this possible? One overarching reason: Karl Ove believes powerfully in what he has to say. This imbues his writing with compulsion and energy.

Naturally, he also bestows powerful desires on his book people. When a character yearns, his yearning sparks the narrative. What do our characters yearn for? Continuation of the same in the face of a threat? Or urgent change? If we convey this yearning in strong declarative sentences, the writing takes on even more energy. Gertrude Stein conveyed the notion of commanding prose in two words: Pour boldly.

And so to the next phase in a particular writing project. We tuck away our latest draft and turn to other assignments. When we return some weeks later to the original work, it appears fresh and new and any changes required will leap out – that sentence is logically in the wrong place; the best word here is oxymoron; this section requires a little unpacking.

But how do we know when our work is good enough for a readership, if it’s a readership we seek? Ideally, we hand it to a trusty writer friend or mentor, experienced readers who don’t baulk before candour and provide the objective input all writers need. Via this input, coupled with extensive reading and some input gleaned from worthy books on the art and craft of writing, we gradually come to know when our work is ready for the marketplace.

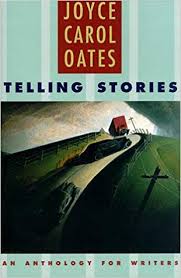

Please step tentatively towards the books in this series. Some will give your writing remarkable impetus. I was tempted to place them into categories: inspiration, nuts and bolts, theory and the like; however, when I tried, the divisions seemed unnatural, for most of the books defy easy labelling. Sure, you might argue that ‘Making Shapely Fiction’ by Jerome Stern is largely a nuts and bolts craft book. Not so, however. Jerome imparts inspired ideas about narrative and so much more.

These books do more than cover the standard ground that naysayers point to when dismissing books on craft. Each offers material that any writer yearning to write better will find entrancingly useful. Let’s begin the journey.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.